Five Pointers for Nocturnal Wildlife Photography

Night time is an incredible time for imaging, a completely different set of critters to encounter. These are my top five tips for successful nocturnal imaging.

Nocturnal wildlife imaging, there can be nothing more rewarding, depressing, exhilarating, or adventurous than donning a headlamp and venturing into the local green space, or in my case, the local jungle to see what critters await. In order to get the best results from my imaging, there are a few things I tend to focus on to ensure the best results. Listed below are the five main pointers I address before, and during, those times when stepping out into the darkness seems like a great idea. Nature is nature though and with the best intention it could always be that you don't encounter that which you set your sights on. It's just part and parcel of this genre of imaging.

1: Know Your Target Range

The Sagaribana night bloom. a 15mm f4 1:1 lens allows me to show the environment around the bloom.

Knowing the critters you expect to encounter will greatly alleviate numerous issues, the main one being the amount of gear, lenses, you opt to carry. I would normally decide on a range of critters I aim to potentially encounter of an evening. Knowing the size of an entity allows you to then decide on the lens you will employ. That said there are other considerations. If you are hoping to photograph a particular species it goes without saying you would need to know their particular environment. Beyond that it is also handy to understand their behavioral calendar. What month do they mate? Do they hibernate? What is their preferred food or prey item? Where is that food source found? The more you know about the environment and lifestyle preferred by your target species the greater your chance of imaging success.

2: The Risk / Reward Analysis

In many regards, there is a risk associated with nocturnal wildlife imaging. For me especially in Okinawa there are a number of critters here that can, if there were so minded, end my very existence should I overstep the mark. Again, knowing the behavioral aspects of your subjects, and in that aspect I focus more on their typical modes of self defense. Here in Okinawa we have not only venomous snakes in the three species of Pit Viper, known as Habu, but we also have venomous spiders, toxic Newts and some poisonous vegetation, and that's only on land!

Knowing your target species in this instance could indeed increase your chance to survive any encounters. For subjects such as Venomous snakes for example I will employ a much longer focal length lens such as a 180mm macro as opposed to when I would be shooting a beetle or a frog for example. Getting away from any potential strike zone is good for me, not to mention my heart!

Another question you should also be mulling over; Is that image needed? Beyond the desire to have that in a portfolio collection is there a shortage of imagery of a possible species that you may have access to? If so that would increase the attractiveness of having that imagery in your archives. Weighing up the pro's and cons of getting the image will then determine if the potential risk in its acquisition would be viable or not.

3: Batteries and Back Up's

When photographing venomous striking snakes such as this Taiwan Habu it's always handy to err on the side of focal length caution.

Best laid plans and all that. Often times I will plan to be out for a few hours to easily find myself overshooting that time frame by sometimes many hours, it just so engrossing. To that extent you should know your gear and the rate of attrition especially for headlamps. Being three hours into the jungle with two hours remaining battery life is not a place I'd like to be knowing the critters I would normally encounter. In less dangerous situations, wildlife wise, there are always terrain specific risks such as pits, ditches and large rocks or fallen trees to possibly contend with.

Check and double check the battery levels of those in your camera and of those in your spares holder. Having dead batteries in either will greatly diminish your nights activities, I've been there, it sucks. As a rule for headlamps I normally go by a very conservative rule based on hourly attrition. Burning at its brightest output I consider a 1hr illumination time. I then set that same illumination period per pack of rechargeable AA cells that I bring along. I travel with what would then offer enough for five hours of illumination. Massive overkill but better safe than sorry.

On a safety planning consideration I always give my wife a pin drop of the location I'm heading to along with a cutoff time by which time I should have contacted her to let her know I'm on my way back. Our agreement is to allow for a one hour window from that cut off time before she rings me. Invariably we always have contact prior to any concerns are raised but it's much better to know that there is a point of contact who 'has your back' so to speak. Don't venture into an unknown region, alone and with no one knowing where you're heading; that indeed is a recipe for disaster.

4: Dress for the Occasion

It goes without saying that the environment will also determine the clothing you wear. Even though it's as hot as balls in the jungle with a humidity index through the roof I always cover up. Mosquitos and other biting critters can dampen any mood especially when some nocturnal wildlife photography subjects require a stealthy approach and steady hand. There's nothing worse than the whine of an approaching mosquito to get the tension levels up. I hope you didn't forget the bug spray? On the reverse side of the coin, those who shoot in much colder climes should always be aware of the risks associated with exposure to low temperatures and take measure to ensure they don't become a statistic.

Here in Okinawa I find myself wearing some form or headwear too given the potential for things to fall from vegetation or indeed engage in aerial attacks. Long cotton and fast dry pants as well as long sleeved cottons and lastly rubber Wellington boots, or 'Wellies' as we call them in the UK. Walking through vegetation at night whilst looking at anything but the vegetation underfoot is simply a way to mitigate any possible issues. Species found here that can bite cannot bite through the durable rubber of said footwear. It may be uncomfortable given the unbearable humidity in the jungles at night time but i'd much prefer to lose a pound or two in perspiration of a night rather than a trip to the local hospital.

The sense of reward when nailing a picture of an endangered species is almost indescribable. A green morph of Ishikawas Frog somewhere in northern Okinawa.

5: To Photograph or to Barbecue?

Nocturnal wildlife has evolved, given its physiological attributes, to occupy that very specific time of day for good reason, to best exploit those assets. It may be that it uses heat sensors to hunt, like snakes, or echo location such as sonar for bats etc. As we foray into the night we bring artificial light sources to enhance our own asset that doesn't perform too well in the darkness, our sense of vision. This in itself brings up the ethical question as to how much flash photography should we expose our photographic subjects to? Let's say we were not to consider that and simply flashed until we'd nailed that shot of a specific subject. In doing so we've thus rendered the night vision of that individual useless to a point it would be defenseless in the darkness once we'd moved on.

As a rule I try to limit flash use on subjects only to a number of shots that are absolutely necessary to get a usable shot. If I can't do that within six or seven shots then I simply back away and hope to encounter another specimen of that species either later in that same evening or on another night. Rome wasn't built in a day. I try as best as possible to have four of the shots taken that will then allow me to focus stack for one rendered image. This allows me to make the best of the limited photographic depth of field to render a nice and clear image of the critter in question.

Multiple images were taken to create this focus stack of a sleeping Tiger Beetle.

Summary

Nocturnal wildlife photography requires an assessment to be made prior to venturing out. Try and come up with a list of those steps given the species you're looking to head out and capture, if possible. This will be determined by the above pointers. Above all this style of imaging can be one of the most rewarding of all, for those of you who like wildlife imaging that is. For me its a chance to kick off the stresses of the day and spend a couple, or three, quality hours in the quiet of the jungles and green spaces of Okinawa.

I've spent a number of years researching and getting accustomed to the behavioral traits of the wildlife here so the jungles are, for me, a place that offers a welcome reprieve, a place where peace of mind is quick to settle me.

Having that level of understanding about your immediate surroundings should also allow you to find that peace of mind when shooting nocturnal wildlife photography. It's not for everyone but when it is shot correctly it can yield some incredible results.

"Adopt the pace of nature: her secret is patience"

Ralph Waldo Emerson

About the Author

Internationally recognized as a provider of quality mixed media Mark Thorpe is always on the search for captivating content.

Photographer / Cameraman

Mark Thorpe

Emmy Award Winning wildlife cameraman and Internationally published landscape photographer Mark Thorpe has been an adventurer since he could walk! Spending 17yrs as an Underwater Cameraman at the start of his imaging career the highlight of which was being contracted to work with National Geographic. In that role as a field producer and cameraman he's been privy to a mixed bag of hair raising adventures. For some reason he was always selected for projects relating to large toothed marine predators such as Great White and Tiger Sharks, Sperm Whales and Fur Seals. Additionally he has also been active within Southern Africa on terrestrial projects dealing with a wide array of iconic wildlife.

Currently based in Okinawa, Japan he's always on the lookout for his next big adventure. He shares his exploits online with a totally organic social audience in excess of 200,000. Sponsored by a number of photographic industry manufacturers he is constantly scouring the islands for captivating landscape and ocean scape compositions. In videography, he continues to create short photographic tutorial videos as well as creating content about the diversity of wildlife within Okinawa and the Ryukyu Islands of Southern Japan.

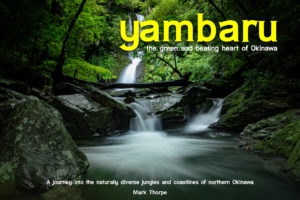

Whenever that rarest of commodities is available, spare time, Mark continues to photograph the flora and fauna of Okinawa that will eventually be used to compile a Coffee Table Book project. 'Yambaru - The Green Beating Heart of Okinawa' is planned to showcase the diversity of wildlife species and landscapes that make up the incredible location known as the Yambaru, the rolling green jungles of Northern Okinawa. Mark has also devised a way for folks to become involved with that project via a support page on the Patreon social platform. For a small monthly donation, used to offset the travel and time to create the book, those willing to are in effect embarking on a 'lay away' project to secure a copy of the book which will also be signed by Mark as a sign of gratitude for the support. More information about this option can be found on the Patreon Profile for the project.

Whenever that rarest of commodities is available, spare time, Mark continues to photograph the flora and fauna of Okinawa that will eventually be used to compile a Coffee Table Book project. 'Yambaru - The Green Beating Heart of Okinawa' is planned to showcase the diversity of wildlife species and landscapes that make up the incredible location known as the Yambaru, the rolling green jungles of Northern Okinawa. Mark has also devised a way for folks to become involved with that project via a support page on the Patreon social platform. For a small monthly donation, used to offset the travel and time to create the book, those willing to are in effect embarking on a 'lay away' project to secure a copy of the book which will also be signed by Mark as a sign of gratitude for the support. More information about this option can be found on the Patreon Profile for the project.